In the latest instalment of “Mick Talks With….”, I sit down and talk shop about hips, specifically the condition femoro-acetabular impingement (FAI) with hip expert, Sports Physiotherapist and Research Fellow Dr Joanne Kemp. For those of you who don’t know Joanne, she has presented extensively on the management of hip pain and OA in Australia and internationally. She has a particular interest in non-surgical, exercise-based interventions that can slow the progression and reduce the symptoms associated with hip pain and OA.

With AFL and soccer (football) such big sports here in Australia, and sports that have such a high prevalence of FAI - I wanted to find out what FAI is, how we diagnose it, how we can treat it and how we can manage it better with our athlete and patients we see in the clinic presenting with FAI. I hope you all find this talk very informative!

Mick: Hi Jo, and thanks for taking time out of your busy schedule to have a chat. I’ll cut straight to the chase. What is FAI?

Jo: No worries Mick. FAI stands for femoroacetabular impingement. Nowadays, we refer to it as FAIS or FAI syndrome. It's important that “S” is added in because to have FAI, you have to have symptoms, and often people in the past have got confused by the morphology (or the shape of the hip that you see with FAI) and the actual clinical condition.

To have FAI you need to have 3 things. Firstly, you need to have pain in your hip/groin region. Secondly, you need to have imaging findings that you typically see in FAI (which can be a number of different things which I’ll discuss later). Lastly, you also need to have the clinical signs, as per clinical tests from a doctor or a physio. If you don't have all of those three things, then you're not considered to have FAI or FAI syndrome.

Mick: What are those symptoms that people should look out for?

Jo: Basically, most people who have FAI will have activity-related pain in the hip and groin region. Sometimes people will also have pain in the buttock area, but usually you will always have that pain at the front.

Mick: You mentioned it before, but what are the key positive clinical examination points of someone with FAI?

Jo: When you look at the clinical exam, you'd look at what we would typically call our “special tests” or our clinical tests. The only test really that's been shown to be useful in using with people with FAI syndrome is the FADIR test - so the Flexion, Adduction, Internal Rotation test.

But it's really important to remember that that test, has a really high sensitivity, so it's good to rule FAI out. That means if you do the test on someone, and they don't have pain when you do the test, then they probably don't have FAI. But it has really poor specificity too, so it's not a good diagnostic test. So, if you do the test on someone and it does hurt, it doesn't really add any value to the information, so they might have FAI, but they might not have. It's important that it's used only as a screening test, but that's really the only special test that's actually useful in these patients.

Clinically, the other things that you look for typically are, they may have reduced range of motion. They may have a reduction in their flexion range of motion, and their internal rotation range of motion compared to the other side, but that's a little bit controversial. Some studies have shown that those with FAI have reduced ROM, and other studies have shown that they don't have it.

The one thing however that studies have consistently shown is that FAI patients have reduced muscular strength in their hip muscles. When you look at all the different muscles around the hip, they are weaker in all of the hip muscles - abductors, adductors, flexors, extensors, internal and external rotators. They're all weak, but in particular, the adductors seem to be the weakest when you look at the impact of FAI on muscle strength.

Functionally, they might also have some other signs like not being able to squat as deeply as someone who doesn't have FAI. They often have poor balance doing stuff on one leg. They're all right if you just stand there, but as soon as you challenge them to do more dynamic tasks like a single leg squat, that sort of stuff, their balance is usually bad and they also tend to go into that typical hip/knee position, and their pelvis drops down on the other side as well.

Mick: Are they looking to avoid pain by doing that?

Jo: It's a good question because the irony is I think they are looking to avoid pain, but when they do something like a single leg squat and they drop down into that valgus position, it's actually increasing their impingement. I think that the bad performance in the squat has got probably got more to do with poor control and poor strength rather than being a pain-avoiding thing.

Mick: So functionally, when they are doing these squatting tasks, will they feel that pain in the front of their groin?

Jo: It's usually activity-related or movement-related. They might get it on some of the tests you do in the clinic. But they might not. They might only get the pain on the activities that they do out of the clinic such as sitting for long periods, pivoting and changing direction, getting down low in their sport.

Mick: So as you mentioned before, features of FAI can be seen on imaging. Does that mean that patients may need to have surgery to correct this impingement?

Jo: That's a good question. In a nutshell, no, it doesn't mean they need to have surgery.

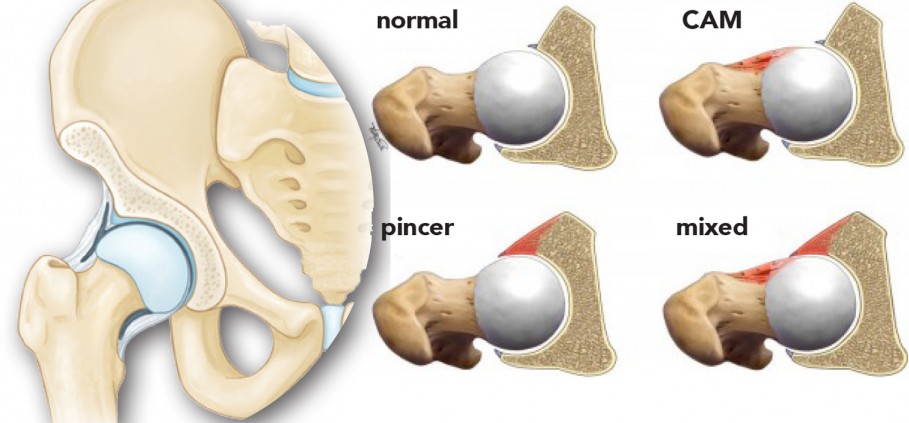

Basically there's three types of FAI. The first type is called Cam type FAI, so referred to the cam morphology, which is the extra bump of bone that you see on the head-neck junction of the femur. The femur normally has that nice sort of round ball shape, and then sort of scoop down on the neck of the femur, and what you see in cam morphology is there's extra bone, so you lose that scooped out shape, it's sort of flattens out. The second type is called Pincer FAI, and that's where the hip socket is too deep. So the socket's either deep all the way around, or the socket's sort of backward facing and retroverted, so it means that it's deeper at the front of the hip, which can cause impingement. And then the third type is Mixed FAI, where you have both the cam and the pincer morphology.

But in terms of surgery for those things, it's interesting when you look at the studies that look at the prevalence of the shapes of hips in people with pain and without pain. Essentially, when you look at groups of athletes, around two-thirds of athletes have Cam morphology, and that's whether they have pain or not. So, Cam morphology in athletes is more related to load and that fact that they're an athlete, rather than whether or not they have pain. In non-athletes the prevalence is a bit higher in people with pain, than without pain, but it’s important to remember that 1/4 to a 1/3 of everybody WITHOUT pain also has Cam morphology.

And the association between cam morphology and pain is not well established, so having cam morphology, or that extra bump of bone is not necessarily associated with actually having pain or having symptoms. So just having a look at that shape and seeing that you've got that bump of bone, it's means that you don't necessarily need to have surgery to take the bone off. It could be that other things other than that impingement shape are the thing that's causing you pain.

Mick: So we know some people eventually do go down the surgical path, does surgery work?

Jo: That's another good question. There's been a whole bunch of case series studies, which are lower-level quality, highly biased studies that show that people do improve from before surgery to after surgery. And just in the last six months or so, there've been two clinical trials published that have compared surgery to non-surgical treatment (physio-based treatment). What those studies showed is that people who have the surgery get a percentage improvement of around 20% after surgery. So even though they are getting a 20% improvement, the big thing that's really important is what a lot of the studies now show is that even though people improve, they don't ever go back to being 100%, or being the same as someone who has never had a hip problem.

And so, it's really important that patients understand that before they go to surgery, that the surgery most likely will give you some improvement, and the average amount of improvement is around 20%, but it's not going to cure you. And I think sometimes people might go into surgery with that expectation that it's going to fix them, and then they're disappointed afterwards when they realize that while they've improved, they're not back to being 100%

Mick: So surgery isn't that successful, and certainly doesn't bring them back to 100%. What role does physiotherapy and strengthening play in the management of FAI?

Jo: So, it can be really important, and I think the thing to remember is in the studies that I just talked about, the clinical trials that looked at surgery where compared to physio, and the physio groups also improved! In one of the studies they improved by about 15%, and in the other study they improved by close to 20%, so the same as the surgery group.

So, what that tells us is that physio can work equally as well as surgery, and so therefore it's really important to try physio first before you go down the path of surgery. Because the surgery obviously costs more, has bigger risks associated with it, and there was a study recently that showed after surgery the patients were more likely to have more co-morbidities - things like not being able to sleep and chronic pain.

I'd always say try physio first before you go to surgery, and if you're going to try physio, it's really important that you look at that impairments that these people have and try and target their treatment to the impairment. Look at things like their muscles, hip muscle strength, their trunk muscle strength, their balance, their ability to do things like single leg squats and step-ups, and that sort of stuff. And really focus on improving their strength, their balance, and their functional performance as well.

Mick: I think when people say that “I have tried physiotherapy and it hasn’t worked” it’s important to find out what “physio” they have received in the past, because I know some patients who have had physio with FAIS, but it's often been passive in its approach (ie. stretching, manual therapy, electrotherapy etc etc).

Jo: It's really important that we delve in deeper and work out, "Well what physio have you done?" And we're trying to get away from calling it “physiotherapy treatment”, but rather calling it "physiotherapist led treatment", or "exercised-based physiotherapist treatment," so it's really clear to the patient what they’re getting in terms of treatment; not just getting passive treatments, but rather an active, progressive approach.

Mick: So my next question was kind of answered before. When it comes to muscle groups; what’s the most important - adductor, or abductor strengthening, or is it both?

Jo: Ideally you do both, but if you manage someone who said, "I'm only going to do one exercise," then you would prioritize the adductor strengthening over the others. But, if you could you would try and target both abductor and adductor strengthening.

Mick: Excellent. So the Copenhagen adductor strengthening exercise? Would that be a recommendation in both rehab, and also injury prevention?

Jo: We use it in our rehab programs definitely as an end-stage adductor strengthening exercise. And I think for athletes it's really important that they can get to the point where they can do that Copenhagen adductor exercise, and if they can't do it, then I would argue they may not be ready to go back to sport. So, definitely include it towards the end stage of rehab programs.

In terms of injury prevention, there was a study, as you probably know, that found that doing the Copenhagen adductor exercise reduces the risk of groin injury by around about 40%, so it does seem to be a really important exercise for groin injuries. Now the problem with that is we can't really specify whether it's hip, like FAI type groin pain or whether it's other types of groin pain. So we don't have definitive evidence of whether the Copenhagen adductor exercise prevents pain in someone who has the potential to get FAI, but my feeling is, we know it reduces the risk of groin injury, so I would definitely include it as a whole team-based injury prevention exercise.

Mick: So no harm having it in there?

Jo: Yeah, that's right. And look, as long as you start sensibly, start early and build someone up so they don't have too much muscle soreness afterwards, then I think yeah, there's definitely no harm in including it, and it may prevent the development of sort of FAI in some athletes.

Mick: In terms of injury prevention for FAI, would there be anything else to consider other than strengthening of the adductors?

Jo: I think athlete screening is something to consider, but the hardest thing is identifying the athlete who will develop FAI and that’s what screening programs are not good at identifying - telling us who's going to get injured and who's not. But where screening is useful is for when someone who comes to you other with a past history of hip and groin pain, then they may be at a greater risk, or if they have some of those shapes that we talked about, they may be at greater risk of getting FAI..

In regards to load management, I think a common sense approach in terms of load management, like you would with any athlete in terms of trying to find that optimal load where you progress them and build them up slowly to get that optimal load, but also trying to reduce the risk of overload, just as much as you want to reduce the risk of under load as well.

And lastly, take a holistic approach with strengthening. Try to strengthen up the whole hip and pelvic area, and the trunk as well.

Mick: Great stuff Jo! So, to finish up, if someone has hip or groin pain and they're suspicious of FAIS, what's the pathway they should take?

Jo: I think probably the first thing to do is to go and see, a sports physio and try and find someone perhaps who has expertise in FAIS, because sometimes you can go down the path of a lot of imaging, and then invasive interventions that you may not necessarily need. The sports physio will do a thorough and comprehensive assessment using some of those things that we just talked about and develop a rehab program for you. You really want to persist with your rehab with a good quality rehab program for a good 3 months or so.

And if you get to the end of that time and you feel really, really confident and your physio feels confident that everyone's done their best, and you still don't have any answers, then that's when you potentially would start to go down the path of getting some imaging, potentially seeing a sport and exercise physician to get their input. Because there may be a role for things like injections. Then your last, final step if all else fails, is to consider surgery. But also going into surgery open and knowing that it's not a 100% cure.

Mick: Thanks very much for your time, I really appreciate it!

To keep up to date with great articles like this one, please consider joining our Learn.Physio mailing list.